The state of the Community Radio Sector in Hungary 2010-2014

The publication of this study in English was supported by: Mertek Media Monitor http://mertek.eu/

Introduction

After the Fidesz-KDNP (Hungarian Civic Alliance - Christian Democratic People's Party) coalition took power in 2010, the entire structure of the Hungarian media was transformed, and extremely centralized. Using its two-third majority, the government adopted a new media law in late 2010, which had been awaited ever since 1996, as there was no consensus between the political parties. 2011 saw the merging of the public service radio (MR), the television (MTV, Duna TV) and the national news agency (MTI) into a single organization (MTVA, i.e. Media Service Support and Asset Management Fund). At the same time, these content providers, which had previously been independent, became the government's mouthpiece. Similarly, the authorities managing media and telecommunications issues were merged under the aegis of NMHH (National Media and Info-communications Authority) (earlier: ORTT, i.e. National Radio and Television Authority and HÍF/NHH, i.e. the National Communications Supervisory Authority/the National Communications Authority). The regional broadcasts and studios of the public media were eliminated rather than strengthened, which was unprecedented in Europe. One of the two national commercial radios (Class FM) came to be owned by Fidesz-affiliated businessmen, while the other one (NEO FM) became competitively disadvantaged, as no state orders for advertisements were extended to it, so it soon declared bankruptcy, then ceased to exist. Then, rather than inviting a new tender, its frequency network was divided between the stations of the public radio, i.e. the public news Radio Kossuth and Radio Dankó, which broadcasts traditional Hungarian melodies. Although the community radio sector that had existed since 1991 and the small community (low power) radio sector operating since 2002 were kept, moreover, they were mentioned in the Media Act as well, the sector received a totally different content than its original purpose, absolutely misunderstanding the "community" character, which distorted this segment of the media market. On the one hand, the frequencies treated as "community" by the administration and usable free of charge are filled up by purely commercial radios, thus creating fierce competition between the community (free) radios run on a voluntary basis and the commercial radios, while on the other hand, the voices of local communities are suppressed by administrative measures one after the other on the low performance frequencies that are still independent. All this is in harmony with the process in which the government intends to centralize the electronic media but not for the purpose of organizational streamlining but for obtaining full control over their content. The elimination of independent local channels is an inevitable consequence of this intention. In our study, we have presented those legal and administrative tools which will, in our view, result in, and we are afraid, are also targeted at the crippling of the community/free radio sector.

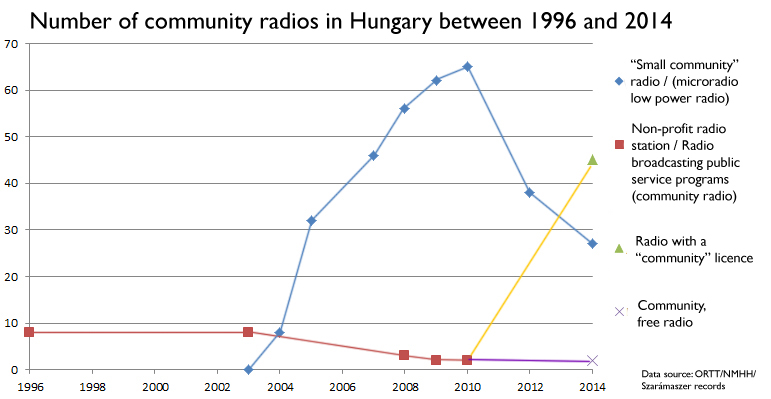

Figure 1: Number of community radios in Hungary between 1996 and 2014. Community radios were listed in the category of non-profit radios, or ones that do not broadcast public service programs in the earlier system. In the newly established system, even purely commercial, non-civil radios are also included in the legal category of "community" (e.g. practically all the radios that broadcast prose programs qualify as community radios), so it may seem that the net number of community radios increased at record speed, to almost the best rate in the world but definitely of Europe (yellow line). It is this rate that the foreign readers perceive from the state statistics. If, however, we consider the genuinely and not de jure "free radios”, we will reach the two free radios that are fighting for their survival on the purple line, i.e. radios Civil and Tilos, while the number of small community radios that can be listened to in a 1-km range has decreased to nearly one third of the original number. Between 1998-2002 and since 2010, it was Fidesz that has ruled, while there was a left-wing government in power between 1994-1998 and 2002-2010.

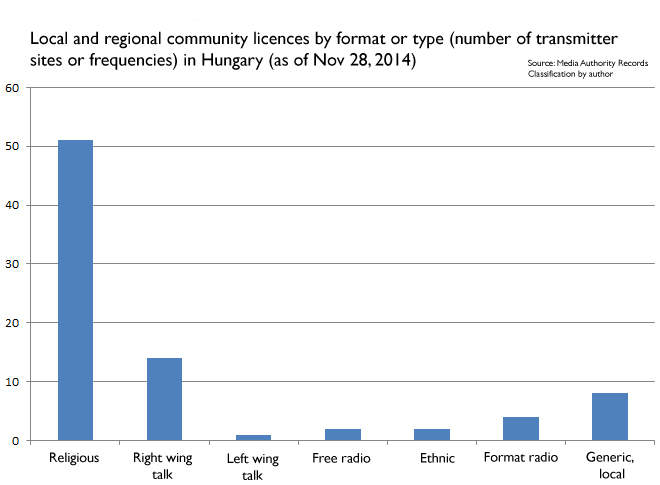

Fig. 2. Number of community frequencies by type or format. Basis of classification: Religious: Europa, Szenti István, Magyar Katolikus, Mária Radio; Right-wing talk: Lánchíd, left-wing talk: Klubrádió. Free radios: Tilos and Civil Rádió (members of the Association of Free Radios). Ethnic: Radio Monoster (slovenian). Format radios: Gazdasági (business news), Inforádió (news-talk), Jazzy and Klasszik Rádió (smooth jazz and classical music), transmitting in Budapest. Generic local stations broadcast a wide range of speech and music programs.

Redefining the concept of "community"

Based on the 2010 Media Act, even radios which have nothing to do with what is meant by community and free radios were awarded "community" status. Although there is a wide range of definitions for community radios in the world, it is unprecedented what is recognized as community by the Hungarian Media Act, and in our view, it witnesses either the lack of understanding of the point of the sector, or too good an understanding thereof.

It is not only the radios that broadcast community programs that are recognized as community radios by the 2010 Media Act but also those which mostly broadcast public service programs (e.g. essentially any kind of speech programs or undefined high standard musical programs ) (Section 66(1)c of the Media Act). The purpose of public service programs is to serve the public, i.e. to serve as wide an audience as possible, that is, everybody, which is exactly the opposite of the community character, i.e. serving a well-defined target audience. The advantage of the community status lies in that the radio does not pay a frequency usage fee, the annual level of which is several hundred thousand or million Forints (. According to the new Media Act, contrary to the earlier regulations, a commercial company may also run a community radio. This is not unprecedented either but the two rules jointly result in that even a radio of a commercial type which broadcasts programs defined as ones for public service may be called a "community" radio station, which is absurd - this is how it can happen that Radio Tilos, which was launched as a pirate radio back in 1991and which is regarded as the figurehead free radio station can compete on the same frequency with the purely commercial radio station called Gazdasági Rádió (on the 90.3 MHz community frequency in October 2014), which broadcasts business news similarly to the US American Bloomberg Radio - as if these two radio stations provided similar services to their listeners. A similarly unorthodox solution was applied when community status was given to the quasi national radio networks in such a way that each of these stations is acknowledged by the authority as a separate radio. In our understanding, the purpose of Fidesz was to show the foreign public in the state statistics that the number of community/civil radios is steeply increasing, while the truly free radio stations are suppressed and the radios working for commercial and political interests are awarded with a community status. If one checks which channels were declared community radio stations on the basis of Note c, Section 66(1) of the Media Act, one will find such stations which would undisputedly be classified as commercial radios in other countries: Inforádió (commercial news radio), Lánchíd Rádió (politically biased right-wing news and talk radio), Klubrádió (politically biased left-wing news and talk radio), Klasszik Rádió (commercial, popular classical music radio), and Gazdasági Rádió (business news radio). None of these radio stations possess any of the criteria of community (in other words, free or civil) radios: all of them are professionally run businesses organized on the basis of commercial and/or political interests, there is no civil community that would act as their target audience, their presenters are not members of the community, they have no voluntary workers, their decisions are not made democratically. Several of them have almost national network coverage. They are the ones to which NMHH's various requirements are tailored and the surviving free radios are incidentally mixed in with them. Thus, purely commercial radios and almost national networks do not have to pay frequency usage fees, and what is more, they they can apply for those state funds which were originally earmarked for the community radios.

The 1-km broadcast range of the 2010 Media Act

After it had been presented in professional documents that the earlier applied 1-km broadcast range means the guaranteed end of the operation of a small community radio, it is still this value that is indicated in the Act. It is very rarely that one can find an entire community within a 1-km range: the residential areas of the employees of institutions, e.g. a school or a village are both larger than this range. Since the geographical realities are disregarded by the Act, only a fraction of a small community can be reached, the radio station cannot fulfill its fundamental purpose, the lack of access reduces motivation and it does not even allow that a radio becomes self-sustaining. Despite this, the lawmakers who adopted the Media Act fossilized the 1-km broadcast range (Section 203(24) of the Media Act), to replace the earlier flexibly applicable official practice.

It is exactly those who live on the periphery, e.g. on the scattered farms of the country whom these radios cannot reach, due to the bureaucrats. It is not possible to lodge appeals or extend frequencies. It is not possible either to launch local, "large community" radios because of the high application fees and the lack of applications for community frequencies invited by the authority (small community frequencies can be applied for by anyone, for any location, while applications for community frequencies are invited by the authority).

Music quotas

Although we regard all kinds of interfering with editorial content as a practice violating the freedom of speech, the quota obligation of the Hungarian musical playlist for all community radios, irrespective of their nature, is outstanding in a global comparison as well - in the basic case (e.g. national online radios), it is 35% (Section 21 (1) of the Media Act), while it is 50% for the community radios (Section 66(4)h). As opposed to this, the local commercial radio stations (which pay to the state) have no music quotas at all (Section 22 (1)d of the Media Act). Thus, besides the government wishing to enforce its nation-building strategy by interfering with the musical editing of civil radios as well, this practice is also applied for the online radio stations that use unrestricted resources, which are not necessarily civil.

It can be an argument for the music quota that in the ether as a limited resource, the broadcasting of Hungarian music is justified in the territory of Hungary (although it is a question why this is not applied for the local commercial radios, a possible answer to which may lie in the local radio lobby) but it is unjustifiable what legal basis the government claims for interfering with the contents of the online radios, which possess unlimited resources.

With regard to the observance of the quotas, it is clear why the online radios also have a reporting and data supply obligation. According to a possible interpretation, the music quota is just an official reason for the total control and thus, intimidation of online (and FM) radios.

Data Reports

It is stipulated in the Media Act that community radios should meet a certain data supply obligation (Sections 66(6) and 22(8) of the Media Act: "The media provider shall supply data to the Media Council on a monthly basis for controlling the observance of the requirements for program quotas.”). This was not defined in detail but was left to the authority to decide what they mean by it. The Media Council of NMHH chose the most brutal solution possible: they regularly control everyone in the form of self-reviews. It is as if every single citizen was obliged to give a detailed report to the police on their daily activities to check whether they have committed a crime. No distinction is made between the data supply obligations of the various radio stations. This could even be set as a positive example for equality before the law but the same burdens were imposed on the national commercial radios with several million Forint revenues, the public media which has a staff of several hundred and the small community radio stations which are run by one person: every single minute of the full broadcast time must be accounted for in such a way that originally 17 (later max. 12) parameters on each prose and music program element have to be specified.

The practice followed by ORTT was that once a year, they requested that the entire material of a randomly selected week be sent in to them as an audio recording and these were listened to by a staff specifically requested to do this job, notes were taken of them, and based on this, it was concluded whether the radios had met their obligations. As such practice is obviously impossible in the form of a continuous 365-day control, the media authority happily delegated the task of data collection to the media providers. The decision was explained by that in the contrary case, the quotas defined in the Media Act and the broadcasting agreement (proportion of Hungarian music, proportion of prose programs, proportion of programs of public service) would not be controllable. We question it from the very start whether it is the only way to ensure the observance of a media law that every single program minute is constantly controlled. We find the administrative burden on the data supply obligation disproportionate to its contribution to public welfare, especially because this burden is passed on by the authority from its own responsibility to that of the broadcasters, by using its official competence. (It should be mentioned here that the argument of disproportionate burden was successfully used by the government in averting the one-time investigation into the potential election fraud.)

Data, i.e. the metadata of each of their program minutes, should be reported on a monthly basis pursuant to the Media Act (Section 22 (8) of the Media Act), however, the Program Monitoring and Analysis Department was greedy enough to instruct the radios to provide weekly data in their first letter, as they said that "this was justified for making the processing of data supply more efficient". (letter of András Mádl from 02.03.2012).

What is more, even such data are and were claimed by the authority as the name of the presenter, the author of the piece of music/words of a song, the title of the album (!!), the genre (!!) of the piece of music and the title of the played musical piece or program (letter of András Mádl, attachment, March 2, 2012 -- the items indicated by (!!) were removed from the claim list later, in 2014), which requirement does not come from the Media Act in any way whatsoever, as this obligation is not broken down to such detail in the Media Act, and the nature of the program element (e.g. whether it is Hungarian) has to be specified as a separate parameter anyway. Thus, the request for too many details is unjustified, which was acknowledged by the authority itself (by an accidental slip in a letter), bringing it up as an argument that if they did not request control data, the radios would provide them with false data (the reason why they request "redundant" data is that they would like to avoid "the widely applied practice" according to which "we provide fabrications instead of data to the music rights protectors" (Balázs Jó's letter to the Association of Free Radios, 23.01.2013)). There is no court in the world that would accept this argument but the broadcasters are helpless against such argumentation.

Discrimination against online radios

Community status can only be awarded to the radios that broadcast into the local ether on FM or those which use cables, or those which broadcast in a 1-km range. As online radio stations are theoretically available to more than 50% of the population of the country, online radios count as national radio stations, so they cannot get a community status, even if the majority of online radios is of the community type, have a well-defined target audience, broadcast programs to various subcultures and reach a wider audience from the start, i.e. they may play a more important role than the small community radios with a 1-km range (the audience of which may be larger in online simulcast than in the 1-km broadcasting range).

Thus, the online radio services that are an organic part of the current media system are excluded by the ruling power both from the list of entities eligible to community and to local radio support. While the funds collected from the commercial media should be used for supporting the community and public service sectors, online media are rejected the community status by using the tricky Media Act, while the music quotas, and with reference to these, the constant data supply requirements are applied for them. In other words, they have no rights, only obligations.

And we have not even mentioned the total chaos surrounding another digital platform, DAB, which is increasingly successful in Western Europe, despite a lot of clumsiness around it.

150% penalty payment

In the overhead cost and technical tenders, the media authority of Fidesz-KDNP introduced a rule according to which, if the applicant for the tender violates either the Media Act or the broadcasting agreement, they will be obliged to repay 150% of the amount received. This is yet another weapon in the intimidation of the communities. Thus, if the share of Hungarian music played on the radio on Christmas day was only 48%, rather than the "committed" 50% in the wording of the agreement, the contract would thus be violated and the authority would "not be in the position to do anything" but launch a procedure against the radio, so the radio station would have to pay back the several million Forint subsidy amount, which they had already spent during the whole year, plus 50%. With such requirements, application for the funds that are redistributed by the state is almost Russian roulette.

Penalty payment, in conjunction with the data supply obligations, basically excludes the genuinely community radios from the scope of eligible applicants, since in order to be able to meet the data supply requirements, an accurately planned broadcast regime, a playlist that possibly consists of few elements but musical pieces that are played many times are necessary, which goes absolutely contrary to the spontaneous mode of operation of community radios, where one musical piece is usually played only once. This means that a kind of counter-selection is built into the system: those radios can apply whose operation is the most similar to that of a commercial radio.

Overcomplicated application system

In 2012, it was written down by the Media Council of NMHH in its own homepage that "Small community radios, which have a tradition of several decades, is one of the symbols of the diversity of the Hungarian media market.” Then they say that "In inviting the tenders, it is also taken into account by the Media Council that the small community radios, due to their limited resources, are not in the position to employ a professional tender-writer, this is why the Council aims to support the applicants by "applicant-friendly" forms and instructions for completion." (30.03.2012) The principles of small community radio tendering were substantially renewed by the Media Council.

Then they created the most brutal tender invitation ever (we should touch wood), in which a total of four applications out of the 21 applications fully met the formal requirements (later one more was accepted, after their having submitted the missing documents) (NMHH decree No. 373/2013 (III.6.)).

(A typical quote goes like: "The applicant is obliged to punch each page of the original tender offer, to stitch some thread through these holes, and to attach a one-time use sticker to the end of the thread on the back sheet of the last page and the sticker should be signed by the applicant's representative in such a way that the signature should extend to the paper").

In 2010, it was promised that the application conditions would be made simpler, however, an application for a community frequency means a 500-page stack of papers, while the overhead application is a 150-page stack of papers.

As a result of this process, the number of small community radios decreased from almost 70 in 2010 to appr. one third of this amount by 2013 (see the diagram at the end of the article).

Formal requirements

The applications should meet so many detailed, uncorrectable formal requirements as if someone had to submit their typed dissertation without any typos. The “Klub rule” is just one of the requirements that reach Kafka-level absurdity, which was first applied against the applications of the oppositionist Klubrádió in 2010-12. (The story, which would have passed as a tragicomedy (Népszava 2013), began by that Klubrádió was declared the winner of a frequency tender by ORTT but the contract should have been entered into after the elections. This was not done by the authority of the newly elected power by having referred to trumped-up issues, the case was then taken to court, where the court, with creative anguish, decided that Klubrádió did not meet the formal requirements because the back sheets of the papers, which are also pages, were not numbered and signed. What the tender invitation contained was that the applicant had to sign each page of the tender offer and the latter should be supplied with "continuous numbering”.) Later, the obligation to sign the empty pages was deemed unlawful by the court, so the formal requirement of crossing the pages was left to the authority, which was by then incorporated into the tender invitations both preliminarily and subsequently, thus, by this absurd requirement, the decision adopted by the court against Klubrádió and favorable for the authority had to be legitimized retrospectively. Since this case was the Media Council's initiation ceremony, now they have to stick to its observance tooth and nail, to the point of irrationality, as it would be them who would become ridiculous if they gave this rule up, although this rule ridicules them anyway.

The requirement to scan the back sheets of unnumbered pages which only contain a slant line (i.e. in the case of a 500-page application, the scanning of 500 empty pages, which are nearly the same and which are crossed by a slant line) recently (2014) kicked out Tilos Rádió from the tender invited for its own frequency.

According to a possible interpretation, this tool is part of the repertoire which was developed by the authority (the Media Council) for rejecting applications that are not to their taste. Furthermore, it is those who usually work for community radios on a voluntary basis who may feel hurt by this unjustified, administrative type of task. Or maybe it is a task similar to a kind of initiation ceremony which is aimed at maintaining the unquestionable authority of the Media Council by succeeding in forcing the applicant to perform some absolutely senseless act before they achieve their desired goal. By any means, the more formal requirements exist, the more chances there will be for making a mistake, i.e. the fewer applications will have to be meaningfully approved.

The application of the Budapest-based Tilos Rádió was rejected with reference to the Klub rule (this time: “the back sheets of the pages were not crossed”), i.e. to only formal reasons but the same reason was indicated in the frequency application of the Székesfehérvár-based Rádió Sansz, which is an independent Christian radio station. In these cases, although a formal “mistake” occurred, it was not possible to lodge an appeal. The lack of the crossed back sheet was the reason why the Székesfehérvár audience can only hear deep silence at the place of the radio that used to broadcast programs between 2006-2013 (at these radios, there are usually no other applicants for the frequency) and at the moment, it is not familiar whether Tilos will disappear from the ether after two decades of operating as the only Hungarian community radio with a significant audience – because of some crossed-over pages.

According to the analysis performed by Mérték Médiaelemző Műhely (Mérték Media Monitor), the card of formal (shape-related) requirements is pulled by NMHH when it comes to competing applications; strangely enough, where there is only one single applicant, there are no formally erroneous submissions. This also suggests that "formal requirements were used by the Media Council as a tool in those tenders where rival applicants appeared. This clearly questions the function of the formal requirements of the tender procedure”. (Polyák and Uszkiewicz 2014)

Delayed tender invitations

It happened several times that the broadcasting agreement of the radios expired but no new small community tenders were invited by NMHH. In such cases, there is nothing that a radio can do, they have to switch off their station, and wait for the tender invitation and approval. This may take as long as even eighteen months. NMHH is not bound by any deadlines or regularity regarding the tender invitations. After the procedure of one and a half years, the applicant may apply again on the same frequency where they used to broadcast before and where nothing was broadcast during this period either by them or another station.

In the case of turned-down applications, the reason for rejection is held back by the authority

Several cases are discussed by radio managers where an application to the authority (the Media Council) was rejected by quoting that it is unacceptable for formal or content-related factors but no specific facts were mentioned in the relevant official letter. If the applicant calls the authority in such a case, the answer that they usually receive will be that "unfortunately we are not in the position to share any information”. The applicant then submits the entire documentation again, they rewrite everything that they deem to have been erroneous and they may be rejected again. It is only through informal connections that one can find out about the real reason for the rejection, so it may turn out that the reason for the turndown may have been a photocopying error or an erroneous invoice (whatever) and no new 50-page text should have been produced.

The obligation to broadcast news

Regular formal news broadcasting became the statutory obligation of community radios (Section 66 (4) a), irrespective of the profile of the specific radio. By this, the radios run by voluntary experts and with low budgets are imposed unbearable burdens. However, some support is also offered for the fulfillment of this obligation: the use of MTI's, which became the mouthpiece of the government, "public service news from their own sources" was made free of charge by the Hungarian government to everybody, including the media providers in 2011 (audio news services should be paid for).

Summary

In today's Hungary, the distribution of broadcasting radio frequencies is about power rather than about the citizens. The distribution of radio frequencies should be an unbiased routine task and not a scandalous process whose outcome to the parties is non-transparent and full of surprises. Today this is such a consciously overcomplicated process which can only be performed by experts possessing outstanding application writing and IT skills with ample experience (the scanning of 500 front sheets and back sheets in the appropriate order and format). For the preparation of metadata required for the official data supply, disproportionately high administration is necessary and special software should be used, although no such experience and knowledge are required for good radio broadcasting. Small community radios are the most important channels for those very listeners for whom the internet or the printed media are unavailable, partially because they are functionally illiterate or they live in extreme poverty, so they have no money to buy a computer and subscribe to the internet. The current system of tenders makes the very tool that would contribute to their becoming informed and socially integrated absolutely unavailable to them.

References

Benedek Gergő - Gosztonyi Gergely - Hargitai Henrik: Kisközösségi rádiózás Magyarországon. Az első 3 év. Civil Szemle, 2007/3-4 pp 123-144.

emasa (2013) Mérték: a Médiatanács újraírja a rádiós piacot. Emasa, 2013. szeptember 19. http://www.emasa.hu/cikk.php?id=10987

Hargitai Henrik - Ferenczi Tünde: Helyzetjelentés a kisközösségi rádiókról 2010. in: Walter András (szerk.): Kisközösségi rádiózás a hazai gyakorlatban 2010. Szabad Rádiók Magyarországi Szervezete, 2010. pp 10-52

Hír24 (2011) Mától ingyenesek az MTI hírei. Hír24, 2011. május 16. http://www.hir24.hu/belfold/2011/05/16/matol-ingyenesek-az-mti-hirei/

IMAR (2014) Jelentések. http://imar-media.eu/jelenteskezelo

Jó Balázs (2013) Levél a Szabad Rádiók Magyarországi Szervezetének az NMHH részéről, 2013. jan. 23. Archiválva: http://szabadradiok.hu/sites/default/files/cikk_files_uploaded/level2013...

Mádl András (2012) Levél a Napszél Kulturális Közhasznú Egyesület részére. Iktatószám: EM/6906-1/2012. 2012. márc. 2. Archiválva: http://szabadradiok.hu/sites/default/files/cikk_files_uploaded/2012_adat...

Médiatanács (2012) A Médiatanács új alapokra helyezte a kisközösségi rádiós pályáztatás elveit. Publikálva: 2012.03.30. 14:10 http://mediatanacs.hu/cikk/3099/A_Mediatanacs_uj_alapokra_helyezte_a_kis...

Médiatanács (2014) A Médiatanács 961/2014. (X. 7.) számú általános érvényű döntése a támogatás-ellenőrzési eljárás során felmerülő szerződésszegések jogkövetkezményeiről)

NMHH (2013a) A Nemzeti Média- és Hírközlési Hatóság Médiatanácsának Pályázati Felhívása kisközösségi rádiós médiaszolgáltatási lehetőségek elvi hasznosítására. Budapest, 2013. április 10. http://nmhh.hu/dokumentum/157361/pf_kiskozossegi.pdf

NMHH (2013b) A Nemzeti Média-és Hírközlési Hatóság Médiatanácsának 373/2013. (III.6.) számú HATÁROZATA. http://mediatanacs.hu/dokumentum/157411/3732013kiskozossegi_eredmeny.pdf

NMHH (2013c) Javul a Kossuth Rádió vételminősége. NMHH, http://nmhh.hu/cikk/161719/Javul_a_Kossuth_Radio_vetelminosege?utm_sourc...

NMHH (2013d) A bíróság jogszerűnek minősítette a Médiatanács döntéseit a „Klubrádió vidéki frekvenciáiról”. Publikálva: 2013.04.23. http://nmhh.hu/cikk/157737/A_birosag_jogszerunek_minositette_a_Mediatana...

NOL (2014) Simicskáé a Class FM. 2014.01.10 06:45 Nol.hu http://nol.hu/belfold/20140110-simicskae_a_class_fm-1437053

Péterfalvi Attila (2014) Levél Dr. Pálffy Ilona részére, ügyiratszám NAIH-703-3/2014/V. , 2014. márc. 17. Archiválva: http://www.naih.hu/files/703_2014_allasfoglalas_ajanloivek_taj_jogrol.pdf

Polyák Gábor – Uszkiewicz Erik: Foglyul ejtett média (Capturing Them Softly). Bp, 2014. http://mertek.eu/sites/default/files/files/szeliden_foglyul_ejteni.pdf

Tilos Rádió (2014) A frekvenciapályázatunk sajtója. http://hirek.tilos.hu/?p=4679

VS (2014) Csuday Gábor: Itt a kapcsolat a Fidesz és a TV2 eladása között. 2014. jan 20. 12:44 http://vs.hu/kozelet/osszes/itt-a-kapcsolat-a-fidesz-es-a-tv2-eladasa-ko...